by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on June 24, 2002

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

The highly pleasing Raga Jog has attracted wide attention in recent times. The old dhrupad, prathama mana Allah, set in the raga and credited to Haji Sujan Khan has been in circulation in the Agra gharana network for the past several decades. Counted among the forebears of the Agra Gharana, Sujan Khan (the Rajput Sujan Singh, before his conversion) was a court musician of Emperor Akbar. Whether Raga Jog actually goes that far back is a matter of conjecture. Perhaps Sujan Khan’s text was adapted to the newly conceived raga at a later time. Be that as it may, Raga Jog is a huge Agra fave and a necessary fixture in that school’s repertory.

Throughout this note M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

Raga Jog

Raga Jog takes Tilang for its base (for Tilang see In the Khamaj Orchard). The Carnatic Raga Nata has some resemblance to Jog’s contours. The key idea here is the insertion of komal gandhar in Tilang’s flow through a vakra avarohi prayoga. Consider the following Tilang phrase:

G M P n P, P N S” n P M G

To that if we add M (S)g–>S there obtains an avirbhava of Raga Jog (“–>” denotes a meend).

Rishab and dhaivat are both absent. The Agra musicians use both nishads thus underscoring its Tilang antecedents. Elsewhere, musicians dispense with shuddha nishad altogether and treat Jog with komal nishad only.

Some key tonal sentences are now written down. We will adopt the bi-nishad version for the purpose of illustration. The frequency of their relative occurrence may vary but the usage almost always adheres to an old Indian principle: when two shades of the same swara are present in a melodic sequence, the higher shade appears in arohi prayogas and the lower shade in avarohi prayogas.

The switch to a single nishad (komal) version is straightforward. The uccharana in Jog is drawn out – almost leisurely – with meends and can barely be conveyed via the written word.

S, S n’ P’, M’ P’ N’ S, g–>S

The meend g–>S is a signpost of Jog.

S G M P, nnPMP, P, M P G, M S (S)g–>S

Pancham is a nyasa swara.

G M P n P N S”, S” G” G” M” (S”)g”–>S”

A typical uttaranga launch.

S”, P n P M P, M P N S”, S” n P M G, G M G–>g–>S

A finely calibrated slide G–>g is deployed.

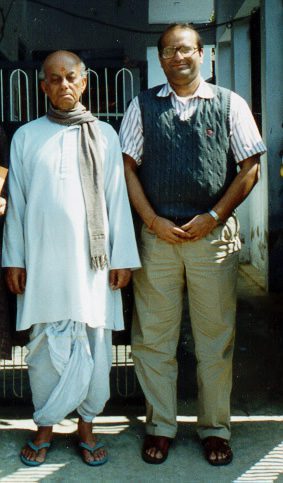

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” and the author (Allahabad, 1999)

Those were the highlights of Raga Jog seen primarily from the perch of the Agra folks. Other musicians have introduced variations. The use of only one nishad (komal) clears the deck for a stronger Kauns anga via, for instance, S, n’-g-S. That, in turn, may be further reinforced by empowering M and displacing P as the location for nyasa. Indeed, this has been the tendency in recent times especially among those wielding the komal nishad-only version. Some argue that this manner of treatment of the ‘original’ Jog de facto turns it into a kind of Jogkauns. This recension of Jog, however, is not only here to stay but is considered the dominant interpretation today.

We set ball rolling with Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.” These ruminations were recorded over the California-Allahabad long-distance telephone line and are compelling, as always.

Lata Mangeshkar’s number from SAWAN (1959) composed by Hansraj Behl: naina dwara se.

No sooner had Jha-sahab touched down in Goa in Dec 2001 than he announced, “do-teen achhi rachanayen abhi bani hai Jog mein, chalo tumko aaj suna denge” (I want to sing to you a couple of compositions in Raga Jog that have recently occurred to me). He explained that he had been “living and breathing Jog” the preceding two weeks. The childlike joy exuded by this great vaggeyakara, now 73 years old, brought to mind the meaning of Einstein‘s memorable words: “Only in Science and Art are we permitted to remain children all our lives.”

These are then the freshly minted (and, as yet, unpublished) compositions Jha-sahab sang that evening. The vilambit, jaanata ho mana ki.

Druta bandish in Teentala, dhare dhyana jogi yati.

Druta bandish in Ektala, avaguna na gino na gino.

Jha-sahab explains the textual import of the preceding compositions.

Jitendra Abhisheki

Jitendra Abhisheki’s inspirited performance at the 1985 Kesarbai Kerkar Samaroh in Panjim, Goa, advertises the Agra view of the bi-nishad Jog. Both the compositions are Ramrang’s older creations, the vilambit Roopak, jane na dehon, and the druta cheez, mori madhaiyya sooni lage ri.

A traditional Agra sortie by Agrawale Vilayat Hussain Khan (“Pranpiya”). He presents Daraspiya’s khayal, peeharva ko biramayo, and then his own ghari pala chhina.

Latafat Hussain Khan assays what is perhaps the most famous composition in Jog, Aftab-e-Mousiqui Faiyyaz Khan’s baby sajana more ghara.

The selfsame cheez by the Goa-born Agra-ite Anjanibai Lolienkar.

The komal nishad-only Jog by the Pandit brothers, Maniram, Pratap Narayan and Banditji.

Vilayat Hussain Khan

Amir Khan’s rendition is komal nishad dominant. Well, almost. Notice the blip of shuddha nishad at 2:07. The vilambit khayal is O balama aba ghara aa’o, the druta is the familiar sajan more ghara.

A dhrupad statement, courtesy Uday Bhawalkar.

The final two items are instrumental selections.

First, Ravi Shankar.

Raga Nandkauns

Nandkauns is a happy marriage of Jog with Malkauns (it bears no relation to Raga Nand). The poorvanga of Jog – S G M, (S)g–>S – is grafted onto Malkauns and a powerful madhyam dominates the proceedings. A sample chalan:

S, (n’)d’ n’, n’ S, S n’ g, g->S

S G G M, G M (n)d (n)d n d, M P G M, S G M P, G M (S)g->S

Parveen Sultana’s recording in Nandkauns is exquisite. The vilambit, vyakula nainana, is followed by paroon tore main paiyyan.

(L-R) Chidanand Nagarkar, K.G. Ginde, Alla Rakha (with

Zakir Hussain), Vilayat Hussain Khan, Azmat Hussain

Khan, Latafat Hussain Khan

Raga Jogkauns

The raga was conceived in the late 1940s by Jagannathbuwa Purohit “Gunidas”. It made a splash on the concert platform in 1951 when Kumar Gandharva signed on as an active protagonist. Gunidas originally referred to his inspiration as simply ‘Kaunshi’ but a subsequent discussion with B.R. Deodhar lead him to re-baptize it “Jogkauns” given its harmonious blend of Jog with the Kauns-anga.

Gunidas’s key insight was to base his melody in Malkauns but with a twist – he advanced shuddha nishad and assigned a cameo to komal nishad. Modern rasikas will say that the melody is based in Chandrakauns but recall that in those days what we now refer to as Chandrakauns was a novelty.

Jogkauns is a masterpiece of musical thought, all the pieces conforming to one another and to an organic whole. Gunidas has been justly credited with fathering one of the greatest melodies of the 20th century.

The core of Jogkauns may be encapsulated in the following prayogas:

S G M P M, M (S)g–>S, G G M, G M (N)d, d N, N S”

S” N S” (N)d, P d n d M P M G M, M (S)g–>S

Notice the powerful role of madhyam. Komal nishad comes along occasionally, bringing a frisson of delight, in a phrase of the type: P d n d (P)M. Shuddha rishab is alpa and may appear as a grace swara as in S G (R)G M.

Jha-sahab offers a concise commentary.

Amir Khan

An early recording in Jogkauns is due to Manik Verma, among Gunidas’s prominent disciples. Gunidas instantiated his vision through two compositions: the vilambit, sughara bara paya, and the druta Teentala bandish, peera parayi, the latter cast in honour of his guru Pranpiya (Agrawale Vilayat Hussain Khan). The text of the druta is as follows:

peera parayi jaane nahin balamava

Pranpiya tuma aise nithura bhaye

‘Gunidas’ ki sari aasa gama’i

The reader may have noticed the introduction of komal nishad (a key lakshana) right away on the first syllable of the mukhdas of both the compositions.

In addition to being a brilliant and highly imaginative musical mind, Gunidas was a devoted teacher (see Appendix below). Another pupil, C.R. Vyas, plies sughara bara paya.

The melody quickly took root and spread across the land. Here we have Husanlal singing it at a Jullandar conference. This is the same Husanlal of the “Husanlal-Bhagatram” composer duo, famous in the 1940s and 1950s for their film scores. Notice here the fleeting but explicit use of shuddha rishab in the tar saptaka (for instance at 0:20). Once again, sughara bara paya.

Vasantrao Deshpande

We round off the Jogkauns session with Vasantrao Deshpande’s crackling rendition of khelana aayo ri and seese ri sehera bandha le.

Raga Chandranandan

This is a baby of the dark and dimunitive (naked) Emperor of San Rafael, Mr. Alubhai Khan. Its constituent elements draw on Nandkauns and Jogkauns, the former to a far greater degree. Once Nandkauns and Jogkauns have been grasped, Chandranandan is then seen as a relatively minor extension, not the stupendous feat of musical legerdemain that Alu would have his firangi minions believe (Indeed, Alu has spun a yarn about how he was challenged to produce something that nobody had heard before). To be sure, some of Alubhai’s bells and whistles under the Chandranandan umbrella are interesting and it must be conceded that in his long lost prime he could whip up an arresting melody.

Alubhai’s 78 rpm recording of Chandranandan.

Some of Alubhai’s “advanced” (biologically) students have been known to mud-wrestle “Shandra-nyen-done” to the ground. Alubhai is encouraged to first instruct the blighters in the art of molesting Malkauns.

Raga Malav

This is an admixture of Jog in the poorvanga and elements of Malkauns elsewhere. The buzz here is a special prayoga involving shuddha dhaivat: P D D n DPM G M.

Jagannathbuwa Purohit “Gunidas”

C.R. Vyas sings the traditional Radhe Radhe in dheema Teentala and then offers a tribute to his guru, Gunidas, via a crisp self-composed cheez, tu hai rangeela mera.

Appendix

See Gunidas.